Communication theory and overlays

When I was studying for the comprehensive exams for my PhD, I studied communication theory. It has become a running joke in my house that my daughter’s early bedtime stories were often research papers instead of fairy tales. [Reading in a gentle voice] “Once upon a time there was a communication model called the Shannon-Weaver model and this model says…”

As the executive director of Accessible Community and the Co-chair of the Accessibility Guidelines Working Group, I spend a lot of time considering solutions to accessibility and where digital accessibility standards are going. Part of that is thinking about how solutions fit into the infrastructure we build in the world. I thought I’d share an “aha” moment I had about overlays and why I believe they ultimately fail to solve the accessibility problem.

As background, “Overlays are a broad term for technologies that aim to improve the accessibility of a website. They apply third-party source code (typically JavaScript) to make improvements to the front-end code of the website” (quoted from the Overlay Fact Sheet). These technologies are added to (overlayed) website code. Often they include a widget for the user to interact with to customize the website.

I should note that this article isn’t about the moral failure of overlay marketing strategies – plenty has been written about that. It’s the result of stepping back and asking the question: “If overlays worked well, where would they fit in the accessibility ecosystem?” And my answer, leaning on communication theory, is not where they sit right now. I will add that this is my opinion and does not reflect the various places I work.

The Shannon-Weaver Model of communication theory is an older model (1948) and academics would rightly argue that a newer model might be a better basis for discussion. However, the beauty of the Shannon-Weaver Model is that it’s easy to understand. Since this is a blog and not a research paper, let’s agree to use the simpler model and move on.

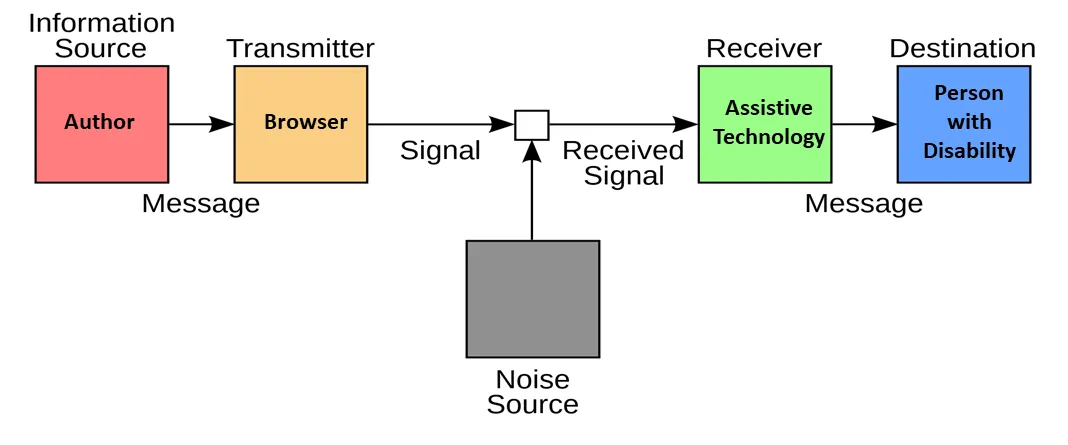

In summary, the Shannon-Weaver Model states that a message is communicated using a Signal that goes from an Information Source through a Transmitter to a Receiver to reach its Destination. The message can be distorted when it is changed into a signal or back again. Noise can be introduced in between the Transmitter and Receiver.

Shannon-Weaver model of communication. Image taken from Wikipedia. Created by aPhlsph7, based on: Shannon communication system.svg by Wanderingstan and Stannered, CC0.

Communication issues occur when the message is sent from the Information Source in a form the Destination can’t perceive or understand.

From a web accessibility ecosystem perspective we can think of this model as follows:

- The author (Information Source) is the person sending the message,

- The browser (Transmitter) presents the message through HTML and CSS (Signal),

- Assistive technology (Receiver) translates the Signal into a form the person with a disability (Destination) can perceive and understand.

The author and browser work together to present information as a signal that can be interpreted by assistive technology. In web accessibility terms, the author and browser create a programmatic signal that the receiver can adapt to various sensory presentations (voice, braille, etc). The goal of a programmatic signal (text in the current technological environment) is to provide as universal a message as possible so that the receiver can translate it. For example:

- Screen readers and text-to-speech take text and change the signal into voice,

- Magnifiers change the color and size of the text,

- Language translation programs and AI convert the text into a form that the destination can understand.

I believe the challenge with overlays is that they attempt to put the translation portion on the wrong side of the communication channel. They attempt to translate the signal being received by assistive technology on the right side of the model, while sitting on top of the transmitter (aka the browser) on the left side of the model. To do this, overlays have to account for all the ways that the signal could be interpreted and send those variations over to the receiver. In short, they add a lot of noise.

In order to work well, overlays should either:

- sit between the author and the browser and help the author create as clean a signal as possible, or

- be used by the receiver as a form of assistive technology.

If overlays were given to authors as a way to improve the message by evaluating pages and suggest corrections for consideration, they could fill a need for an intuitive way for novices to create accessible pages. If overlays were provided to people with disabilities as a way to better understand the message that was sent, they could add to the suite of tools individuals with disabilities have to perceive and understand content. Giving control of overlays to people with disabilities would reduce the noise they create in their current position.